Is virtual water the problem solver for Kenya?

Kenya has a population of just under 55 million people, however over 43% of those do not have access to fresh, clean water on a daily basis. Unsurprisingly, the lack of water has also reduced the opportunity to grow sustainable crops, and with the agricultural industry providing around one third of the nation’s income, eruptions of violence have occurred as pressure increases to sustain the country’s population. The water crisis in Kenya does not just impact the agricultural industry, access to clean water is also a major concern, particularly for maternal care. Unfortunately, the Kakamega Provincial District General Hospital has been forced to provide its patients with polluted buckets of water, causing an increase in typhoid and diphtheria, exposing how the water crisis impacts all.

Kenya’s story of water insecurity becomes even more complicated when one considers how more than 80% of the region is arid or semi-arid, with a mere 17% of the country considered to have high agricultural potential. According to the UN, Kenya’s population will rise to 160 million by 2100. If this occurs, water resources are expected to drop to 192 m3 per capita. This is an exceedingly low level compared to Falkenmark’s understanding that around 1000 m3 per capita per year is needed to sustain an adequate diet, also being the threshold for chronic water shortage. However, one must consider how Kenya typically uses green water resources to grow crops.

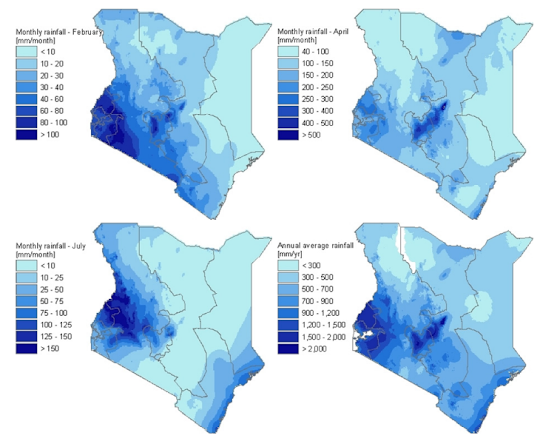

Kenya also experiences large temporal and spatial variability in rainfall, with a wet season often in the West during February. The drastic ranges in rainfall across the country and year, paired with the high level of crop water requirements in the semi-arid and arid parts of the country, impedes much of the land being suitable for rain-fed crops. Accessing and utilising green water is challenging and expensive as groundwater recharge is minimal, therefore, should Kenya turn to the virtual water trade to solve the water crisis?

Virtual water import is a method which allows a nation to save scarce domestic water resources. For Kenya, the country imports water-intensive products and exports commodities that needed minimal water to produce. The other side of the concept permits water-abundant countries to profit by exporting their water-intensive commodities, creating an economic cycle as well as balancing water requirements. Kenya is not self sufficient in producing food due to climatic conditions explained above, so, 72% of rice, 63% of wheat and 10% of Kenya's maize is imported.

In contrast, Kenya’s

horticultural industry is particularly strong, with

flowers generating the highest economic returns per unit of water exported.

At

the same time, coffee and tea exports have significantly grown, suggesting

how Kenya is shifting towards creating an agricultural sector which is not

self-sufficient but rather focuses on exporting high-value crops. Not only can

we see here the strategy to mitigate water insecurity via global trading but

also how this concept creates jobs, with tea cultivation directly improving employment.

The figure below visualises how coffee and tea export has continued on an

increasing linear trajectory, proving prosperous for the nation.

Kenya’s production and import of cereals (maize, rice and wheat) and export of coffee and tea.

Overall, the virtual water trade appears like a prosperous and profitable route for Kenya. However, unfortunately it is not as simple as this and raises the question of whether water should continue to be prioritised for the growth of products including flowers and coffee or should it be reserved to produce essential foods such as maize? One appears to come at the consequence of the other and there is no simple way out. For policy makers, they must consider the economic and social impacts for all and the longevity of the virtual water trade industry.

Can Kenya rely on the export of flowers and coffee and import of cereals forever? Or rather is this a sustainable way to improve and utilise the land to create economic returns? On the other hand, should they turn to mitigating and creating ways to harness the local green and blue water to manage food production for themselves? There are many factors to consider and with accelerating consequences of climate change and increasing population, the race is on to stabilise Kenya’s food and water.

This was an interesting read. I also did some research into this topic and as you say, there are indeed many factors to consider when considering the potential implementation of a VWT strategy for Kenya - especially weighing up the different social and economic benefits. I was wondering whether you personally think this would be a good strategy for Kenya to adopt?

ReplyDeleteHi Emma, thank you for your response. I think the Virtual Water Trade may be a possibility for Kenya to effectively stabilise its water and food production. It is definitely a positive how much money the flower industry brings in. However, there are issues with reliability and whether this is a sustainable way, with pros and cons to the trade.

DeleteI enjoyed reading this post and agree with your argument that surely there comes a point when Kenya must work to improve and utilise their own land. One thing with virtual water (especially in Kenya since, as you stated, 72% of rice, 63% of wheat and 10% of Kenya's maize is imported), is this fosters a situation of dependency and neocolonialism. Do you agree that this is something Kenya should work to avoid falling back into?

ReplyDelete