Integrated Water Resource Management in South Africa

The demand for freshwater provision is evident across multiple African countries, with one of my earlier blog posts touching on the Virtual Water Trade as one way Kenya attempts to stabilise its needs. This week, I shall be looking at the presence of Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) strategies in South Africa, exploring how the nation works to provide water and food security.

According

to UNESCO, IWRM is a holistic approach to water management, seeking to

integrate the management of the physical environment within broader socio-economic

and political frameworks. Since the 1992 World Summit on

Sustainable Development, IWRM has been praised to effectively manage river

basins, becoming sensitive to local ideologies and political understandings. The UN suggests

that in the case of an environment which has a shortage of freshwater, specialised

IWRM systems should be developed. Specifically, these should focus on drought

preparedness and the need to manage food scarcity through water re-use in

agriculture. This is very much the case for South Africa, with a continually growing

and urbanising population, food security is vital.

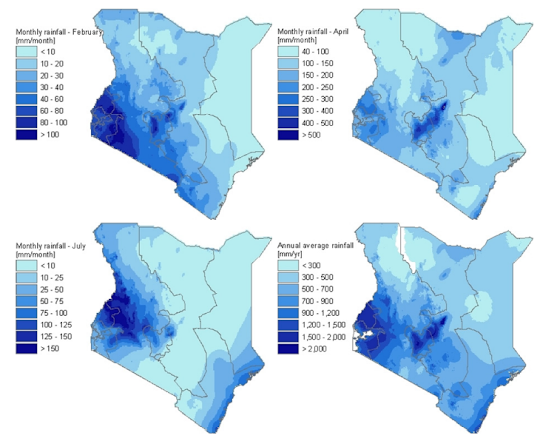

Historically, South Africa met demands for water consumption, with communities in the higher eastern areas depending on rain-fed agriculture and hunter-gatherer communities in the drier western province adapting to the variable temporal and geographic patterns of rainfall to sustain their crops and animals. However, in the early 20th century modern agricultural practices accelerated in popularity, with these monoculture methods more intensive and demanding vast amounts of water.

Initially,

the No. 54 Water Act of 1956, prioritised reducing pollution of freshwater resources

to maintain their use in farming and for domestic purposes. However, this emphasised

the role of the state and institutional players, serving as

an aid to the catalyst of industrial expansion which centred on capturing

and storing water safely through industrial developments. This included the instalments of boreholes (at the time this would have taken around 9 months) to access groundwater storage. This meant that

although IWRM tactics were used, the main focus was on infrastructural developments.

After the apartheid was abolished and water demand increased, social and economic issues became increasingly complex in the mid-1990s. The global paradigm for water resource management was shifting from supply side engineering solutions to demand side management, with South Africa recognising that engineering solutions which aimed to increase water supply for agricultural and domestic use were not sustainable in the long term.

As significant

political change occurred, the National

Water Act stressed the need for water management and regulation at both a

national and catchment scale, urging the need for equitable water use. At this

stage we see the shift towards the IWRM practices we know today, with the development

of laws increasing the chances of effectively managing the nations dwindling water

supply. This fostered a focus on improving

management between stakeholders and communities across South Africa, such

as utilising and managing the transboundary Limpopo River Basin which lies across the northern boarder of South Africa.

Although IWRM in South Africa has increased engagement

between all sectors of the economy as to how to manage and distribute water it

is not all positive. The looming, prejudiced perceptions from the apartheid still

exist within South African politics and culture, with those living in Townships

(specifically in Cape Town) often excluded from decision making practices (the

repercussions of the anticipated Day Zero left residents in restricted water

use –25 litres, which in the largest Township Khayelitsha is the daily average amount

most families use anyway). South Africa continues to work on how to reduce

the economic and social gap between White and Black communities, integrating

and educating communities on how to manage their water supply on a local level for

farming practices whilst implement top-down strategies to maintain city life.

Hi Silke! Really enjoyed reading this and found it very informative. I was interested to know how effective the 1954 Water Act has been, especially if there have been more infrastructure projects going on. How has pollution been reduced?

ReplyDelete