Zimbabwe’s volatile relationship with food security

The discussion of Zimbabwe’s food security is extensive and historically complex, with the nation suffering years of explosive political discrepancies. To gather a holistic understanding of Zimbabwe’s food security, it is crucial to recognise the legacy of colonialism and political instability this created. The radical redistribution of land began in the early1980s via the implementation of the Lancaster Agreement and called an end to the Rhodesian Bush War. The theory behind the land distribution stemmed from years of inequality between white and black farmers in Zimbabwe, with the goal to reorganise the land equally amongst farmers and transfer land ownership back to the majority blacks. However, unsurprisingly, this was not a simple process and unfortunately lead to years of corrupt government control and an intensification of farming on malnourished land, generating a decrease in crop yields. Land reform strategies ranged from market-based including the ‘willing seller-willing buyer’ imperative in the 1980s, to Fast Track Land Reform in the early 2000s which overall left hundreds of thousands displaced. Land cultivation strategies depleted as many farm owners were not specialised in successful and regenerative practices.

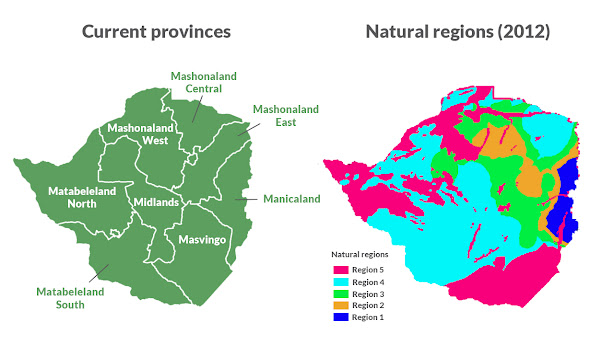

Prior to years of conflict,

Zimbabwe’s natural land provided a profitable environment for farming

and food production, with the country split into five areas ranging from the Eastern Highlands District which due to its high elevation and high average rainfall (above1,000 mm per year) provided perfect conditions for coffee, livestock and tea

farms to flourish, to the intensive farming of Harare that gained seasonal summer

rainfall to effectively produce the Maize crop. Although there are large variations

in climatic conditions across Zimbabwe, the mild subtropical climate and seasonal rainfall allowed for the development of successful farms which helped to stabilise

malnutrition across much of Southern Africa.

20 years on from the land distribution plans, Zimbabwe faces a new, arguably more threatening issue – climate change. Unfortunately, the impact of climate change on the agricultural industry is very much real. Edward Chikanga works on Lake Kariba (known to be one of the most prosperous lakes and reservoirs in the world) as a tourist guide and fisherman.

Naturally, he recounts how the lake has seen variations in

the water level over the years due to seasonal rainfall patterns and water

usage. However, during the long-lasting drought in 2015, exacerbated by El-Nino

oscillations, lake levels plunged. The reduced rainfall upstream diminished

the flow of rivers feeding Lake Kariba. For Edward and others, this drastically

impacted their fishing abilities, reduced water levels meant the fish travelled

further out into the lake to deeper water. However, the equipment needed to fish

in these deeper waters is expensive and hard to source. Climate change has severely

impacted Zimbabwe’s fishing community, with individuals like Edward witnessing

the change first hand.

Furthermore, it is not just the fishing

community which has been hit with changes to their production, agricultural

farming has too. After the United Nations World Food Program suggested the number of food insecure Zimbabweans is

estimated to have surged to around 60% of the population (8.6 million) at the

end of 2020 due to the combined impacts of economic recession deriving from

political imbalance, drought and the Covid-19 pandemic, the government

implemented the Pfumyudza project. Ultimately, the aim is to climate proof farming techniques on small scale farms to create high yields at a local scale, thus providing household food security.

The government is providing farmers with an initial input package and expects the farmers to plant their crop in time for the expected rainy season and where possible create plots near water sources. As this scheme is on a small-scale basis, farmers are projected to be able to irrigate their crops by hand and meet their household demands, with the rest of their produce contributing to the National Strategic Grain Reserve (stockpile to utilise in future crisis).

However, the scheme has been criticised

as not providing long term solutions, and rather, is irrigation the greater

issue? How will these farms maintain themselves during periods of El-Nino when the

drought season intensifies? Not only have issues of longevity arisen, but local governments have apparently been distributed packs to only their supporters, with certain community members often excluded. Unfortunately, this impacts women and

children who are the most vulnerable during pregnancy and the early stages

of life to malnutrition. It seems Zimbabwe has returned to the outstanding

issues of political control and inequality which are preventing the nation from

meeting demands for a growing population in an ever-changing world.

Finding solutions to both political

tensions which still linger and returning to a state of food security is imperative

for Zimbabwe. However, unless the government manages to stabilise engrained

prejudices and political disputes, food and water security appears a secondary issue.

Good attempt at explaining a complex intersection of history, politics, geograohy and food insecurity in relation to water in Zimbabwe. I was wondering how local residents are adapting to food insecurity and potential water stress beyond government intervention. Also, good embeding of literature.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Clement. I have come across research conducted on the Mazungunye community in the Masvingo Province, looking at the challenges faced forthis rural community as climate change accelerates, putting a strain on the agriculture industry which sustains their livelihoods. It became apparent that local, oral knowledge is a strong part of the community, with locals educating others on what, when and where crops grow best. It also suggested the imperative for policy makers to help rural people by further educating them on effective strategies, suggesting a unity between the government and communities is essential, although these communities can educate themselves, there must be a push from top-down processes too.

DeleteThis is the link of the article I read:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6407465/

I enjoyed reading you post and think you really touched upon everything. The situation of fishing seems a significant one since it is not just climate change, drought a reduced rainfall that makes fishing 20 years on difficult but also the ability to source and finance equipment. This applies I'm sure to many crops across the Zimbabwe.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment! Yes, that is definitely the case - there are multiple factors which lead into this topic, including human and physical elements. As you said, this is the case across Zimbabwe and other countries in Africa.

Delete