Genetically modified crops part 2 - Ethiopia

Productivity, equitability and sustainability. Three factors which should be addressed when discussing the development of a new product or infrastructure. These notions are therefore applicable for analysing the costs and benefits of genetically modified (GM) crops in Ethiopia which I will be discussing this week following on from my last post.

At a first glance, the main use of GM crops is to provide a solution for food insecurity and hunger, increasing food consumption in countries which struggle to provide for their communities. For Ethiopia, most a farmers are identified as subsistence (produce crops or raise livestock adequate for only their personal consumption, with no involvement trading or selling their goods) or otherwise known as peasant farmers. With around 12 million peasant farmers in Ethiopia, boosting productivity is one of their main goals. GM crops offer a way to do this by reducing the chances of a harvest being lost due to pesticides, freeing up more money for farmers to invest or purchase more seeds.

Subsistence farmer in Ethiopia utilising animals to aid the harvesting process

However, when reviewing the concept of equitability in GM farming, the discussion becomes more convoluted. Unfortunately, land equitability in the agricultural sector of Ethiopia is particularly low with most of the benefits going to state-owned farmland. On an everyday basis, peasant subsistent farmers work with lower-quality land with reduced productivity, thus unable to bring their harvest to the market and when they are able to, rural markets have prices 70% lower than larger urban markets. Therefore, peasants do not have the capital to invest in stronger seeds, healthier land or irrigation systems, trapping them in a cycle of deprivation.

However, Ethiopia has experienced land reform strategies to close the gap between richer and poorer farmers across the country (exacerbating the intertwined relationship between food security and political policy), since 1991 small-scale farmers are able to lease land from the local government.

GM crops

are still a relatively new concept, and primarily still in their experimental

stage with organisations like TELA

Maize trialling farms across Ethiopia. If they become commercially accessible,

it is

likely only the wealthier farmers who can afford such technological innovations

will utilise GM crops. This,

paired with the patent rights which would require the purchasing of new seeds seasonally,

peasant farmers would be unlikely to maintain using the products long term.

Traditional, rural market in Dorze, Southern Ethiopia

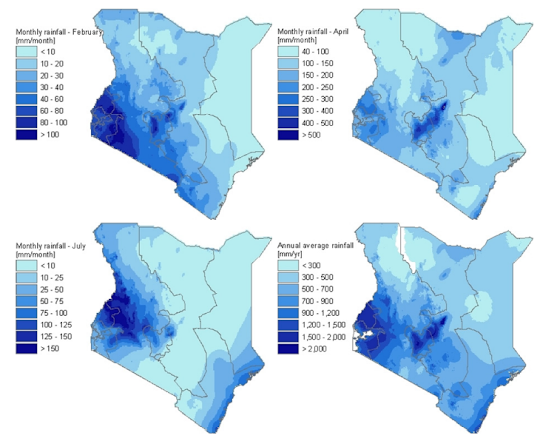

Other than GM crops desiring to be equitable and enhancing productivity, one of the prominent discussions within the field is if they will become a sustainable way for Ethiopia to become food secure in a time of climate vulnerability. Agricultural sustainability is defined by a crops ability to cope with environmental change. Current crops run by peasant farmers cannot survive throughout the long periods of drought and overuse of small farming land has lead to degradation, with farmers prioritising short-term survival rather than long-term sustainability. Secondly, only 5% of peasant farmers work with irrigated land, the remaining 95% rely on seasonal rainfall. This exposes how GM crops may not be a sustainable means of development for Ethiopia as they would not be taken on by smallholder farmers, as even if they had access to seeds, the optimal rainfall cannot be met naturally, thus restricting who is able to benefit from them.

Is

it more feasible then to recognise that GM crops may be part of the solution of

food security, but not the whole picture? GM

crops have the ability to enhance productivity and be a sustainable way of

solving the per capita food insecurity through large state-owned farms. Furthermore, biotechnology

is a method which can most definitely increase crop yields and protects crops (to an extent) during

unprecedented weather conditions, but

for it to reach the mass market and provide a large percentage of the

population with jobs, the government must invest in subsistence farmers and help them acquire the strategies to make GM farming feasible and sustainable on their land.

In my next post, we will be moving down the east coast of Africa to explore the Usanga Wetlands in Tanzania and the balancing act the country is experiencing to protect the land from degradation but also create a healthy food supply!

Comments

Post a Comment